The Optimal Stopping Problem: Testing the 37% rule.

While reading chapter one of the book Algorithms to Live By: The Computer Science of Human Decisions I came across an interesting problem with an interesting solution, The Secretary Problem, the problem statement is as follows

Imagine an administrator who wants to hire the best secretary out of n rankable applicants for a position. The applicants are interviewed one by one in random order. A decision about each particular applicant is to be made immediately after the interview. Once rejected, an applicant cannot be recalled. During the interview, the administrator gains information sufficient to rank the applicant among all applicants interviewed so far but is unaware of the quality of yet unseen applicants. The question is about the optimal strategy (stopping rule) to maximise the probability of selecting the best applicant.

Here are some inferences from the problem statement.

- The applicants are interviewed in random order.

- You can decide to select an applicant on the spot, if you decide to pass over the applicant, you cannot go back and select them.

- You are “unaware of the quality of the yet unseen applicant”. This implies that you do not have any information other than how the applicants you have interviewed so far compare to each other. If that condition was absent, then you can tell if you have interviewed an applicant that is exceptional and you do not want to risk losing him and thus hire him immediately.

A solution to this problem as stated in the book is that you should select the best candidate only after considering about 37% of the total candidates.

So if you have 100 candidates, you should interview the first 37 candidates, take note of the best one of them but don’t hire him and then moving forward you should select any candidate that is better than the best candidate you have seen so far.

The solution looked simplistic to me, and I thought it would stand a high chance of not getting the best candidate. The solution also states that this method would lead to selecting the single best candidate about 37% of the time, you can check the wikipedia article for the details.

In this article, I would attempt to test the rule by running two simulations of the problem, one with 100 applicants and another with 1000 applicants. We would rely on the Law of Large Numbers for our experiment by running the simulation 1 million times. We would also check the result for other stopping points, particularly integers between 1 and 100.

We would judge the result of the experiment based on the following criteria

- The total number of times the best candidate is selected for the 1 million times that the experiment would be run should be maximum when we select the next best candidate after considering 37% of the total applicants.

- For other stoppage points further away from 37%, there should be a considerable drop in the total number of times the best candidate is selected.

To simulate the solution to the problem I wrote a Kotlin script that models the Secretary and their interview performance as an integer value

data class Secretary(val value: Int)

the performance of one secretary compared to another would be determined by comparing its value with the other secretary.

The function to simulate the selection process is shown below

fun simulateFindingBestSecretary(percentageToLeap: Int): Boolean {

if (percentageToLeap <= 0 || percentageToLeap > 100) {

error("Percentage to leap must be between 1-100")

}

val numberOfSecretaries = 1000

val leapValue = percentageToLeap * (numberOfSecretaries / 100)

val allSecretaries = (1..numberOfSecretaries).shuffled().map { value ->

Secretary(value)

}

val bestSecretaryFromFirst37Percent =

allSecretaries.take(leapValue).maxByOrNull {

it.value

}!!

val selectedSecretary = allSecretaries.takeLast(numberOfSecretaries - leapValue).firstOrNull { secretary ->

secretary.value > bestSecretaryFromFirst37Percent.value

} ?: allSecretaries.last()

return selectedSecretary.value == numberOfSecretaries

}

The function has an argument percentageToLeap: Int which could be a value between 1-100, this would enable us to run the experiment for different stopping points.

What the function does is select the best candidate from the first n per cent of candidates and then checks the rest of the pool of candidates to see if there is a candidate that is better than the best candidate we have so far, if we find any candidate we pick that one, if we do not find any candidate we just select the last person we interview.

To change the number of applicants in the pool, just set the variable val numberOfSecretaries

to whatever value you want.

Then we run the simulation for each stopping point 1 million times and save the number of times the best candidate was selected for each stopping point in the IntArray resultArray

fun main() {

val resultArray = IntArray(100) {

0

}

for (percent in 1..100) {

for (x in 1..1000000) {

if (simulateFindingBestSecretary(percent)) {

resultArray[percent - 1]++

}

}

println(resultArray.contentToString())

}

}

The complete code for the experiment can be found in this GitHub gist

Result:

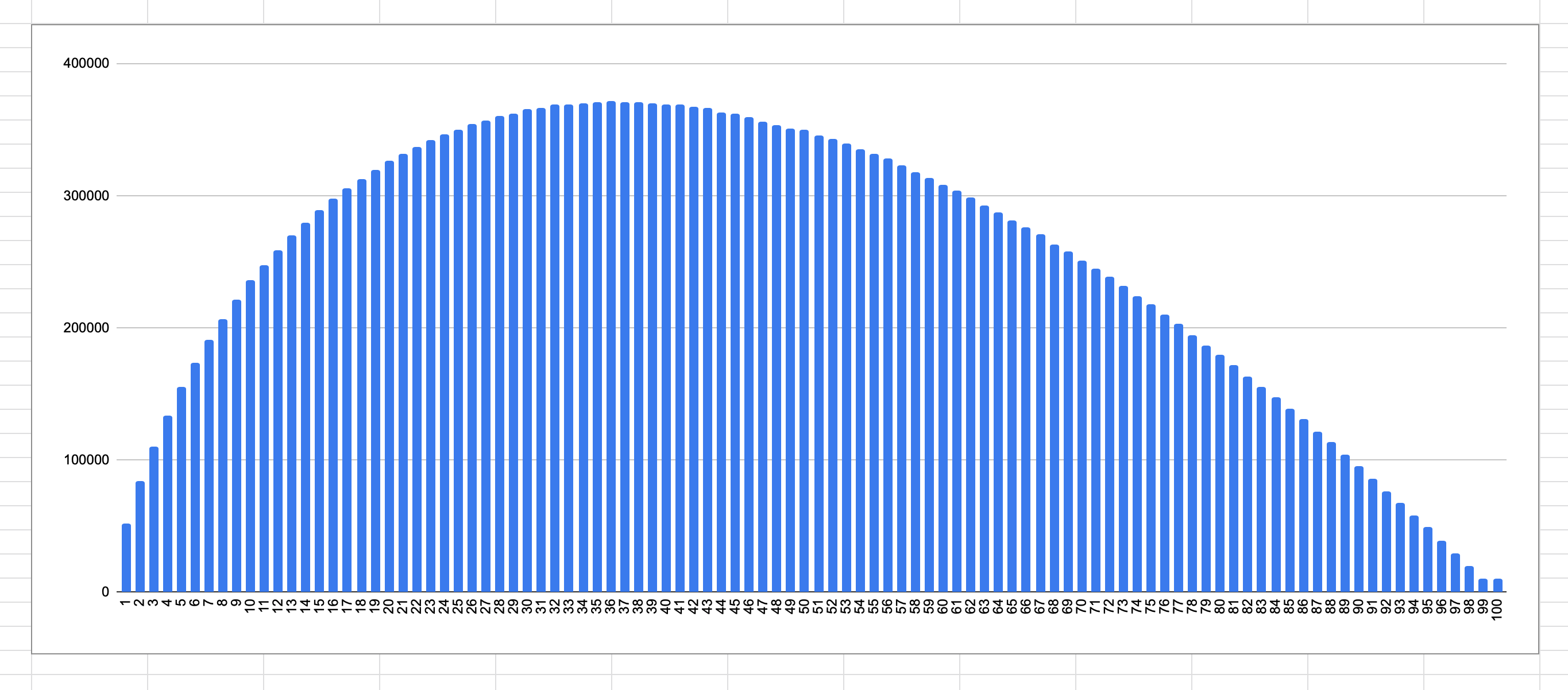

I have plotted the result of the experiment on a column chart below

-

100 Applicants:

For the simulation with 100 applicants, I got the start below and the maximum number of times the best candidate was selected for all the stoppages was 371238 this happened when we selected 36% of the candidate as the stopping point.

-

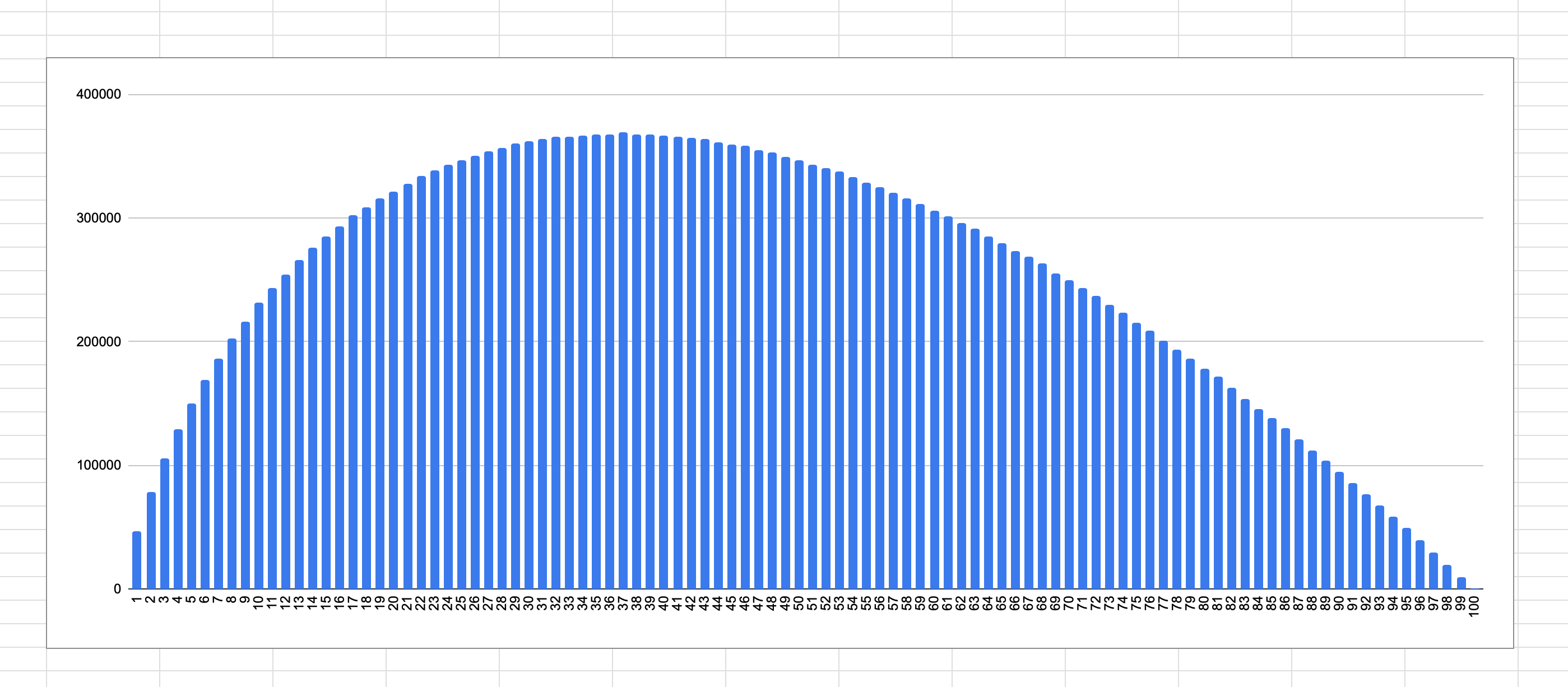

1000 Applicants

With 1000 applicants the maximum time the best applicant was selected was 369144 and this happened when we stopped searching after interviewing 37% of the applicants.

Link to Spreadsheet of result and graph

The result from the two simulations and the resulting graphs shows meets the judging criteria that we mentioned earlier

- The total number of times the best candidate is selected for the 1 million times the experiment was run should be maximum when we select the next best candidate after considering 37% of the total applicants.

- For other stoppage points further away from 37%, there should be a considerable drop in the total number of times the best candidate is selected.

Point two is apparent from the shape of the graph, points farther away from the 37% mark have less likelihood of yielding the best result.

Conclusion

A 37% chance of making the correct decision might be relatively low especially for decisions that we would have to make once, also, the problem statement for the Secretary problem is a simplified version of most of The Optimal Stopping Problem, we would face but it is still fascinating that there are simple mathematical solutions to decision-making problems like this. Some other variations to the problem and their solution can be found in the Wikipedia article.